Shouting Secrets

is a story of a splintered Indian family trying to connect in a time of

crisis. It is the first feature film by Korinna Sehringer, and stars

some of Indian country’s leading talent, both veteran and up-and-coming.

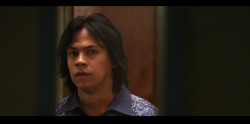

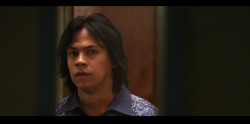

Siblings Wesley (Chaske Spencer), Pinti (Q’orianka Kilcher) and Tushka

(Tyler Christopher) must get along with their father Cal (Gil

Birmingham) when their mother June (Tantoo Cardinal) becomes seriously

ill. Each of the kids is finding their way in the world, some

fumblingly: Wesley has become successful and famous for writing a

tell-all book about growing up on the rez; Tushka is in a failing

marriage and straying; Pinti is pregnant with a white underachiever’s

baby.

The film debuted at the American Indian Film Festival, where it won the award for Best Film. Days before that first screening, Indian Country Today Media Network spoke with Korinna Sehringer as she was putting the final touches on the print at her home base in Munich, Germany.

How did you, a Swiss-born, Europe-based filmmaker, come to make a movie about American Indians?

We were searching for a universal family story. This story could happen with a family at the North Pole, South Africa, Venezuela. And since it’s a universal story, we said, let’s put it in a setting that we’re not so familiar with.

So you didn’t start out with an inherently Native story—how did you go about putting it in that setting?

I started writing it with Mickey Blaine,a young Caucasian writer I had met through a mutual friend in L.A. I saw his one woman show “pipe dreams” which was simply amazing writing work and his ultra low budget feature “Commit” and decided to work with him because I felt he is very talented. He wrote the first 4 drafts of the script. The story is his. I felt the story and script needed a better dramatic structure and the humor needed to come out through the culture. That’s were Steven Judd [Kiowa/Choctaw] and Tvli Jacob [Choctaw] came in and did a great job. It was a fruitful collaboration and one could not have done without the other. I thought it was interesting to see that especially the scenes where the Caucasian and the Native American cultures collide turned out to be the funniest. Steven and Tvli could tell me, “Yes, that’s what we are, those are our jokes, this is our culture.” And we put so many jokes into the script—when we did our last table reading, we were dying laughing. A lot of those jokes didn’t end up in the film; the film we made is definitely a family drama. It has some humor in it, and it’s overall a hopeful story.

What were your guiding principles for assembling what turned out to be a very impressive cast?

We did extensive research for casting. I wanted fresh faces, but faces with experience. I found Q’orianka Kilcher through a YouTube clip. And then when I was interviewing her, I asked for recommendations and she suggested Chaske Spencer. Tantoo Cardinal was the exception; she’s the grande dame of Native cinema. Getting her for this film was our dream.

How did you find shooting on the San Carlos Apache Reservation?

The reservation is an incredible mix of beauty and hardship; for a filmmaker it’s fascinating because of that contrast. We didn’t have to change anything. We found a family that would let us shoot on their property. This 50-person crew shows up, invading their living space, and yet—they were cooking for us. They made us frybread. And then suddenly the neighbors are cooking frybread, and then they made a soup and had everybody over for dinner. And it was delicious.

Were there any drawbacks to shooting on reservation lands?

It wasn’t really a drawback, but one time I wanted to shoot a scene in a particular location and was told I couldn’t film there because it was sacred. That turned out to be a really lucky development, because it made us look for another location, and when we did, we found one that is just stunningly beautiful. It was perfect—better than the original spot—for what is really a climactic scene in the movie.

What—if anything—do you feel this film could accomplish, culturally speaking?

There’s a preconception that today the Native Americans who live on the reservations all have drug problems or are all alcoholics. This movie can show that’s a misconception. Yes, there are problems, but these are people trying to live their lives. White people have problems too. When the cast read the script, they were like, Yes—finally we can play real people, we don’t have to ride a horse or be alcoholics.

The film debuted at the American Indian Film Festival, where it won the award for Best Film. Days before that first screening, Indian Country Today Media Network spoke with Korinna Sehringer as she was putting the final touches on the print at her home base in Munich, Germany.

How did you, a Swiss-born, Europe-based filmmaker, come to make a movie about American Indians?

We were searching for a universal family story. This story could happen with a family at the North Pole, South Africa, Venezuela. And since it’s a universal story, we said, let’s put it in a setting that we’re not so familiar with.

So you didn’t start out with an inherently Native story—how did you go about putting it in that setting?

I started writing it with Mickey Blaine,a young Caucasian writer I had met through a mutual friend in L.A. I saw his one woman show “pipe dreams” which was simply amazing writing work and his ultra low budget feature “Commit” and decided to work with him because I felt he is very talented. He wrote the first 4 drafts of the script. The story is his. I felt the story and script needed a better dramatic structure and the humor needed to come out through the culture. That’s were Steven Judd [Kiowa/Choctaw] and Tvli Jacob [Choctaw] came in and did a great job. It was a fruitful collaboration and one could not have done without the other. I thought it was interesting to see that especially the scenes where the Caucasian and the Native American cultures collide turned out to be the funniest. Steven and Tvli could tell me, “Yes, that’s what we are, those are our jokes, this is our culture.” And we put so many jokes into the script—when we did our last table reading, we were dying laughing. A lot of those jokes didn’t end up in the film; the film we made is definitely a family drama. It has some humor in it, and it’s overall a hopeful story.

What were your guiding principles for assembling what turned out to be a very impressive cast?

We did extensive research for casting. I wanted fresh faces, but faces with experience. I found Q’orianka Kilcher through a YouTube clip. And then when I was interviewing her, I asked for recommendations and she suggested Chaske Spencer. Tantoo Cardinal was the exception; she’s the grande dame of Native cinema. Getting her for this film was our dream.

How did you find shooting on the San Carlos Apache Reservation?

The reservation is an incredible mix of beauty and hardship; for a filmmaker it’s fascinating because of that contrast. We didn’t have to change anything. We found a family that would let us shoot on their property. This 50-person crew shows up, invading their living space, and yet—they were cooking for us. They made us frybread. And then suddenly the neighbors are cooking frybread, and then they made a soup and had everybody over for dinner. And it was delicious.

Were there any drawbacks to shooting on reservation lands?

It wasn’t really a drawback, but one time I wanted to shoot a scene in a particular location and was told I couldn’t film there because it was sacred. That turned out to be a really lucky development, because it made us look for another location, and when we did, we found one that is just stunningly beautiful. It was perfect—better than the original spot—for what is really a climactic scene in the movie.

What—if anything—do you feel this film could accomplish, culturally speaking?

There’s a preconception that today the Native Americans who live on the reservations all have drug problems or are all alcoholics. This movie can show that’s a misconception. Yes, there are problems, but these are people trying to live their lives. White people have problems too. When the cast read the script, they were like, Yes—finally we can play real people, we don’t have to ride a horse or be alcoholics.

No comments:

Post a Comment